News & Events

Guest Author

Neil Constable, Chief Executive, Shakespeare’s Globe. Photographer, Simon Kane.

Shakespeare: from Shoreditch to Southwark

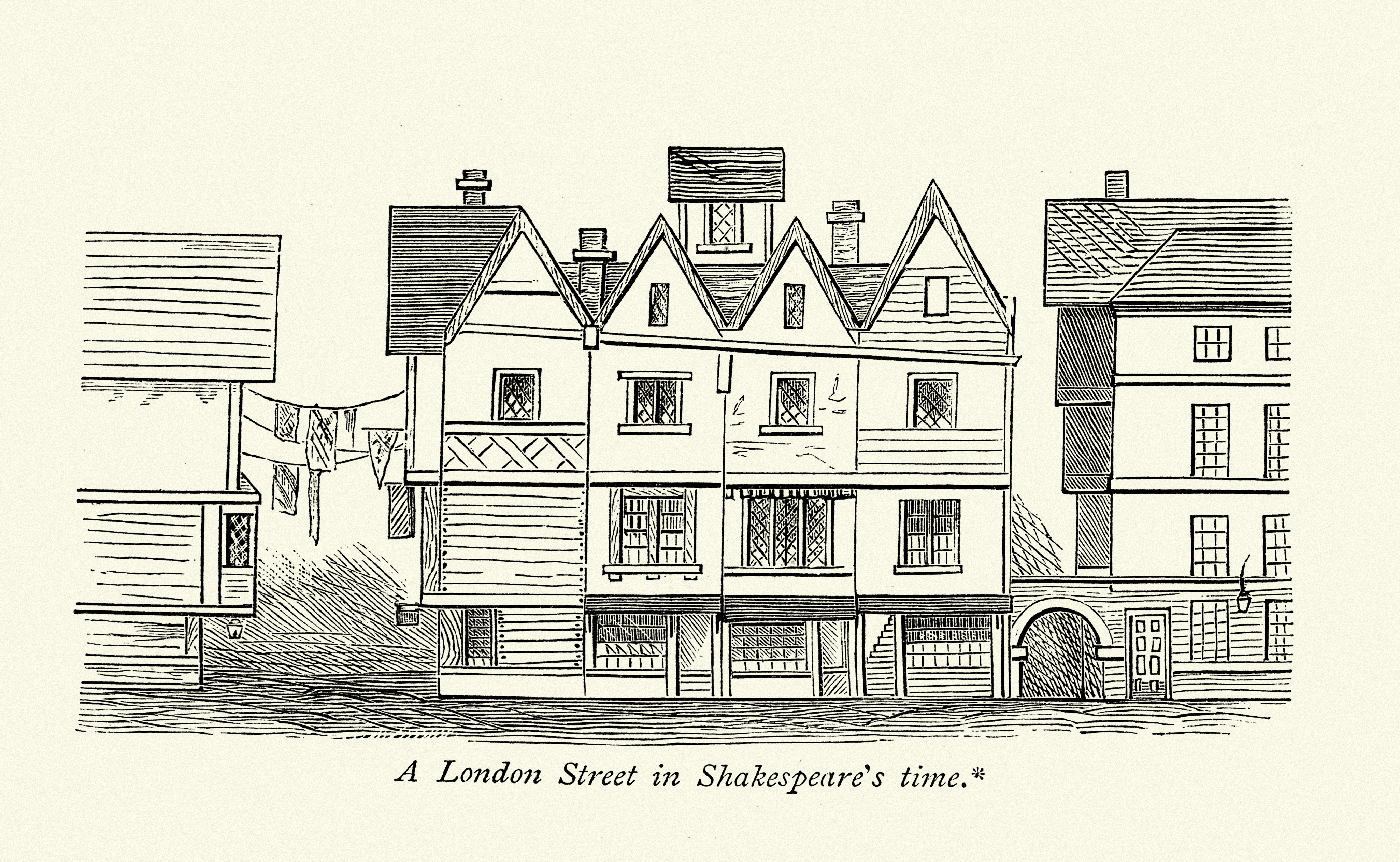

Shakespeare’s London was, as you’d expect, very different from our own—Covent (or ‘Convent’) Garden was a tumbledown veg patch, London Bridge was London’s only river crossing, and the City lay within the perimeters of an ancient Roman brick wall (fragments of which can be found at Tower Hill). To the west sat Westminster, then a separate municipality connected to London by the Strand. To the south of the City and across the River Thames lay Southwark, a neighbourhood where many City laws did not reach. Here on London’s outskirts you could expect to find playing, animal baiting, prostitution, drinking, and gambling. To the north-east was Shoreditch, which, similarly free of the jurisdiction of the London city government, was home to taverns, brothels, and dicing-houses that were frequented by those persons the Privy Council considered ‘dissolute, loose, and insolent’.

Shoreditch (or ‘Sewersditch’) was also home to London’s first playhouses and, until the 1580s, was the chief theatrical quarter. Following fears that unruly crowds could spread plague, playhouses were not allowed within the city walls and it was in the northern suburb that impresarios built the Theatre (1576) and the Curtain (1577).

These two playhouses were Shakespeare’s first professional homes. It was at the Curtain that Shakespeare’s company premiered Henry V and staged plays such as Romeo and Juliet, Much Ado about Nothing, and Henry IV Parts 1 and 2. It wasn’t until 1599 that the company took up residence at the newly constructed Globe, over the river on Bankside. We don’t know for sure which of Shakespeare’s plays was the first to be written for the Globe. It might have been Julius Caesar, or As You Like It. The famous reference to the ‘wooden O’ in the Prologue to Henry V has long sparked questions as to where the play was originally staged, and the excavation of the Curtain’s rectangular shape (not a ‘wooden O’ as was previously believed) has already begun to shed new light on the subject. I am sure this is just the first of a number of special discoveries that this space has to offer as its stories continue to be uncovered. The Curtain site and the rebuilt Globe will remain in dialogue as they continue to reveal what these new/old theatres can tell us about the old/new ways of experiencing Shakespeare.

About the author

Neil Constable is the Chief Executive of Shakespeare’s Globe and was named in 2017 as the joint 10th most influential person working in the performing arts.